Epistemic Injustice: Why Do Certain Voices Remain Unheard in Research?

Why are some forms of knowledge considered legitimate, while others are silenced? Why are some people listened to and recognized as experts, while others must constantly prove that they are? These questions lie at the heart of what is known as epistemic injustice.

The term was introduced by philosopher Miranda Fricker in 2007 to describe the ways in which injustice shapes the production and recognition of knowledge. Two main forms are often identified:

- Testimonial injustice occurs when someone is perceived as lacking credibility due to their social identity—such as race, gender, age, etc.

- Hermeneutical injustice arises when a social group lacks access to the language, concepts, or interpretive tools needed to articulate and validate their own experiences. This often happens because their realities differ from those of dominant groups, whose experiences are more extensively studied and understood. As a result, the experiences of marginalized groups remain unseen, unheard, and misinterpreted by broader society. It emerges when we lack the collective tools to name or make sense of a lived experience—often because dominant groups have never had to face it themselves.

In both cases, these forms of injustice obstruct the full recognition of marginalized groups as legitimate knowledge holders and producers.

When Partnership-Based Research Reproduces Inequality

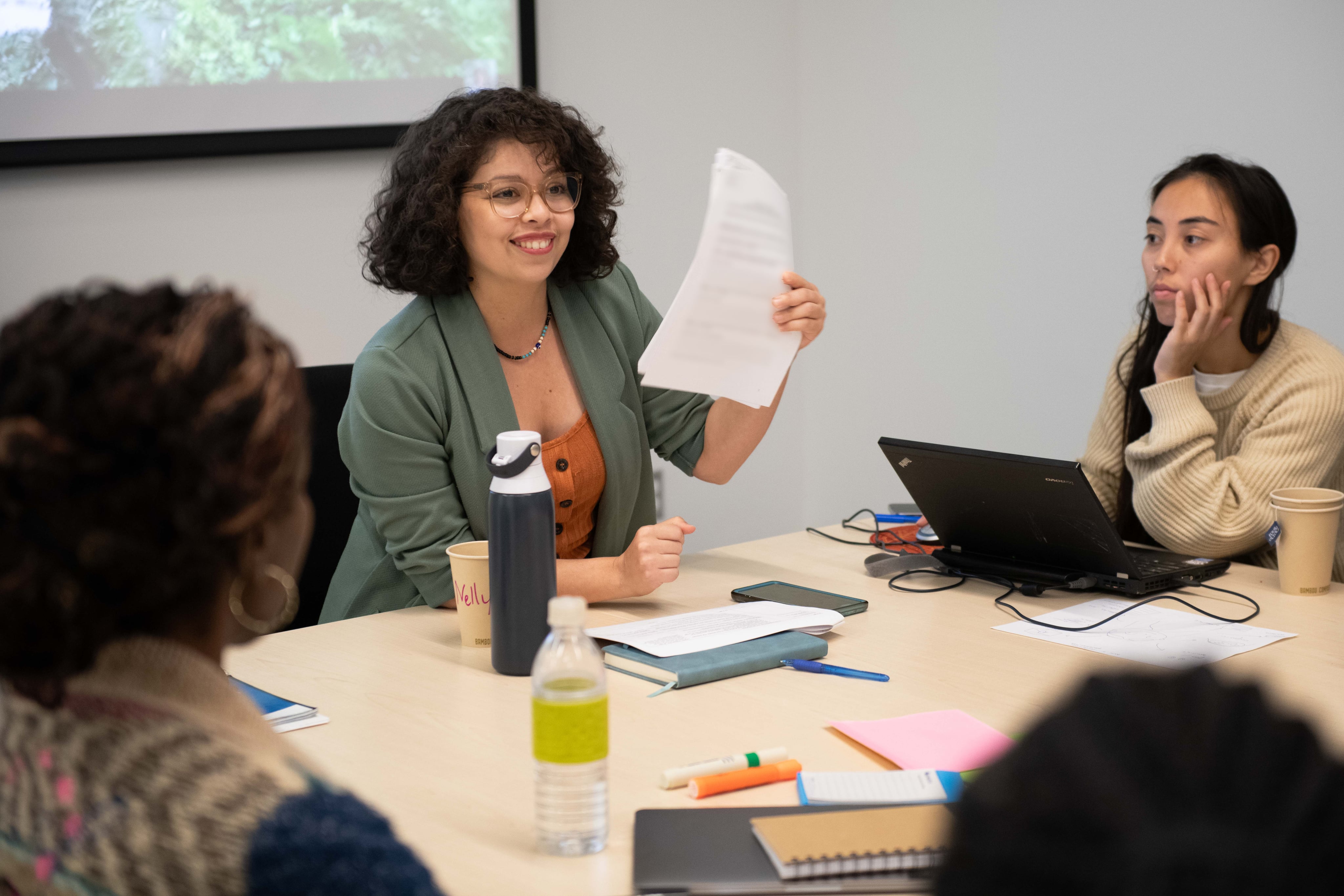

One might assume that partnership-based research—with its stated commitment to collaboration and inclusion—would be shielded from such dynamics. Yet the PARR project reveals that these forms of injustice persist—even (and sometimes especially) within initiatives that describe themselves as “inclusive.”

Several participants shared feeling instrumentalized for their networks or lived experiences, without meaningful acknowledgment of their intellectual contributions. Others described being dismissed—or met with surprise—when they offered relevant insights.

That surprise—that implicit reluctance to recognize Black and racialized women and non-binary people as producers or co-producers of knowledge—is no accident. It reflects a long-standing history in which the norms of “scientific knowledge” have been shaped by and for dominant groups.

Testimonies gathered through the research and the podcast En fleurs, Plus en feu ! reveal a deep exhaustion: the constant need to justify one’s presence, to navigate between community precarity and academic hostility, and to witness one’s ideas taken up without credit or recognition. As Chloé explains of her doctoral experience: “Often, I’m the only Black person. […] And in those spaces, there’s a heavy silence that makes it even harder to speak.”

This marginalization goes beyond exclusion. It involves a persistent devaluation—where voices may be permitted but are rarely taken seriously or carried forward in the work that follows.

Those Who Know

These injustices don’t arise in a vacuum. They are rooted in deeply entrenched stereotypes embedded in the collective imagination and reinforced by dominant societal narratives. As François Toutée¹, then a master’s student in philosophy at UQAM, analyzed, stigmatizing discourses—that associate certain groups with negative traits—undermine the credibility granted to members of those groups. In an academic world where neutrality and objectivity are tightly controlled and often mythologized, marginalized voices that challenge these narratives are more readily dismissed as subjective or politically motivated.

Even when these stories are heard, they are often instrumentalized. The white academic may walk away with a publication, recognition, or funding—while Black or racialized participants see their knowledge co-opted and their role reduced to that of victims or mere objects of study.

Recognizing epistemic injustice means first refusing to reduce certain people to research subjects. It means affirming that their lived experiences, language, and interpretations are legitimate forms of knowledge—and that this knowledge can and should guide decisions, directions, and methods.

Towards Truly Transformative Research

Certain practices can resist erasure. For example, life stories, when received with respect, can become powerful catalysts for transformation. By making visible experiences that are deeply rooted in the lives of those involved, they help validate forms of knowledge that are often dismissed or overlooked. However, this requires time, attentive listening, and spaces intentionally designed to ensure the safety and dignity of those who share their stories.

Read the article on ethical practices and by-for-with methodologies

¹ Toutée, François. 2018. « Les coûts épistémiques de la haine : Discours stigmatisants, injustices épistémiques et liberté d’expression. » Dans Émancipation et philosophie. Sous la direction d’Audrey Paquet, 71-87. Montréal: Les Cahiers d'Ithaque.

Some excerpts are drawn from testimonies in the PSRR report or from the reflective card game. These have been adapted and anonymized for outreach purposes.

Promotion des actrices racisées en recherche (PARR). (2024). Strategies in bloom: Cultivate your well-being in collaborative research (Reflective card deck - English version). A tool for raising awareness and self-reflection, based on the testimonials and transformation ideas shared as part of the PARR project.

The definition of epistemic injustice is taken from the PARR report, which quotes Godrie, B., Desrosières, E., & al. (2020). Les injustices épistémiques : vers une reconnaissance des savoirs marginalisés.