Changing the Rules in Research: Knowledge, Justice, and Responsibility

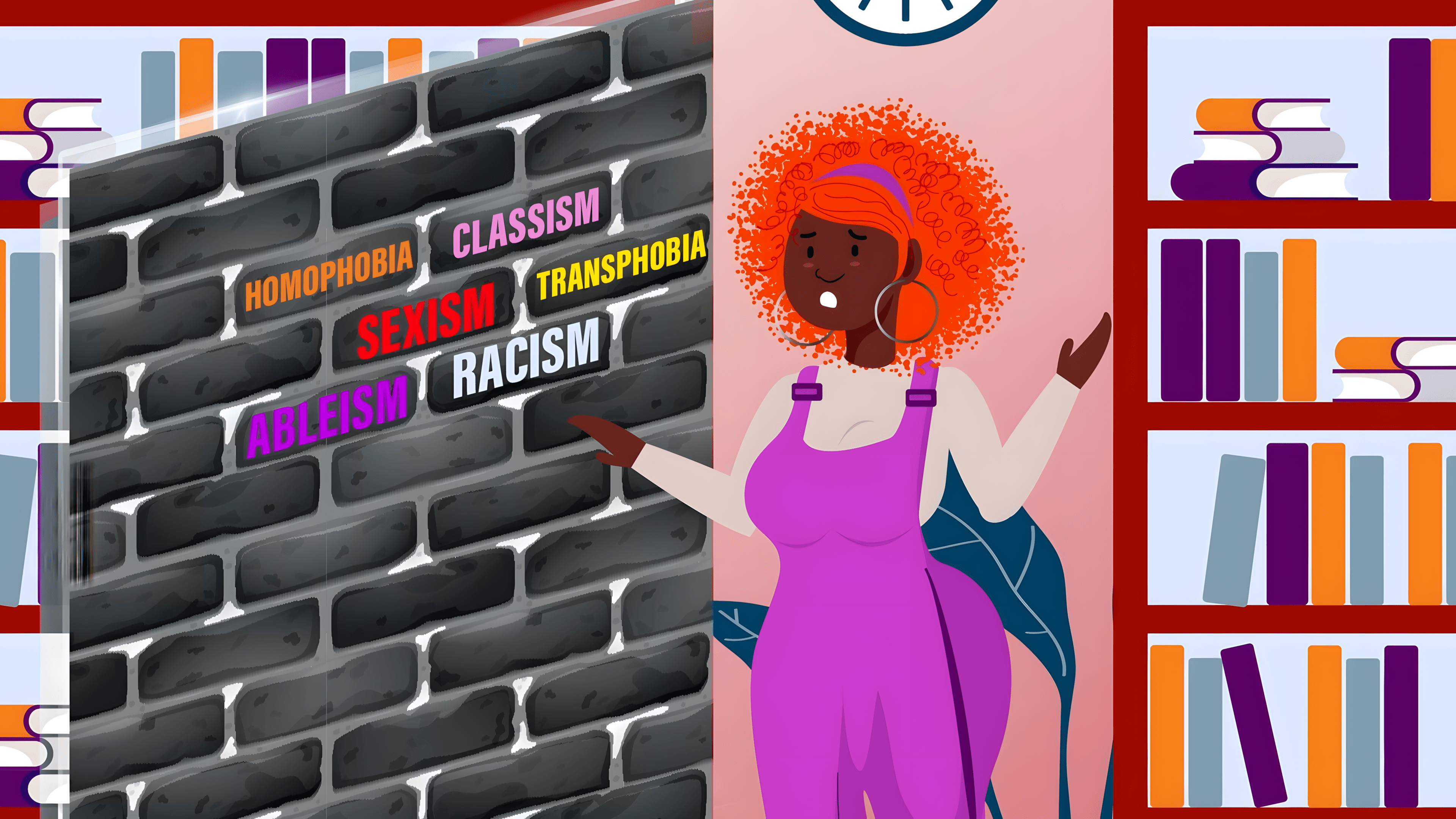

Knowledge is never neutral—it is shaped by political, social, and emotional contexts. Its production is always influenced by power dynamics. Adopting an anti-oppressive approach to research is not about virtue signalling or ideological posturing; it is essential to genuinely understand lived experiences and prevent the reproduction of the very systems of oppression our research so often seeks to interrogate.

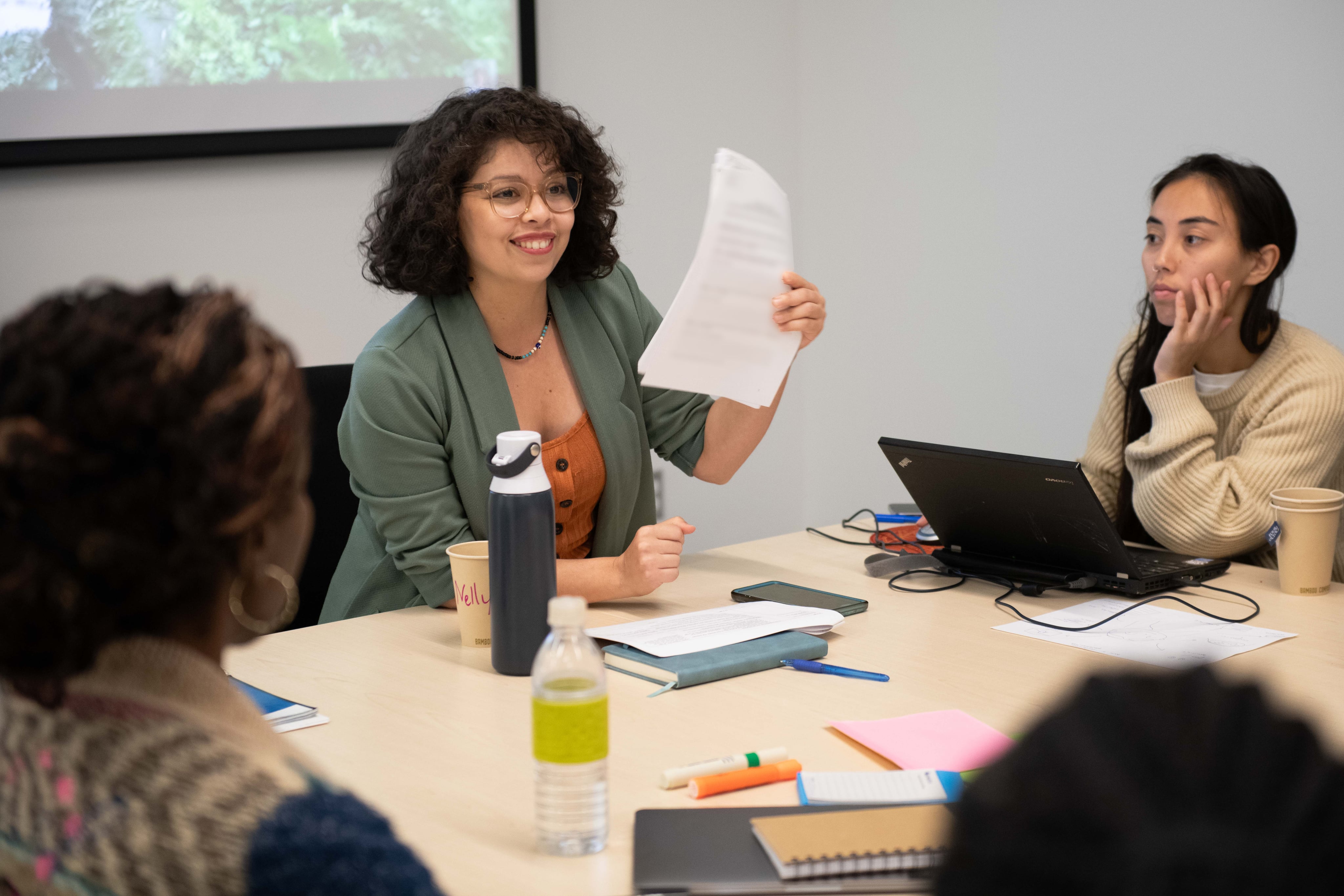

In research, this means engaging differently. It calls for research done by, for, and with communities. It requires recognizing that these communities are not merely objects of study but knowledge holders and active participants throughout the process.

Rethinking Ethics Through an Intersectional Lens

Unlike conventional academic ethics processes that often focus solely on individual protection, an anti-oppression approach also requires considering the preservation of communities. When the PARR project chose to establish its own independent community ethics committee as part of its research, it was a refusal to let universities alone decide the value or legitimacy of the knowledge produced. Researchers Félicia Cá and Saaz Taher discuss this in episode 1 of the PARR podcast. The aim wasn’t to lower ethical standards, but to ground ethics in a broader understanding—one that embraces collective risks, power dynamics, and the need for a framework created by and for the communities involved.

Resisting Knowledge Extractivism

In far too many projects, the contributions of Black and racialized women and people with marginalized gender identities are reduced to the extraction of their testimonies and knowledge—without meaningful recognition or reciprocity. Participants in the PARR project widely criticized this extractive approach to knowledge, as it perpetuates colonial dynamics. Taking without consent is pillaging.

Protecting your knowledge, safeguarding your networks and community, and asserting your right to say no is a political act. If a project fails to offer respectful and meaningful benefits to the community involved, refusing to participate is not only legitimate—it is necessary. Practising ethical gatekeeping means recognizing that your contacts, experience, and network are not commodities to be sold or offered as tokens of goodwill or inclusion.

Making Space: Compensation, Support, and Creating the Right Conditions

A person’s participation—especially someone from marginalized communities—cannot be reduced to a mere invitation. It demands concrete conditions, such as providing translation services, adapting language for accessibility, fairly compensating contributions, and sharing results in formats that are useful and tailored to the needs of the communities involved.

Without these concrete measures, the claim to “give voice” risks becoming a disguised form of exclusion. Making knowledge accessible, understandable, and usable is not a mere administrative detail—it is a profound ethical responsibility. It is also crucial to acknowledge the community’s contributions to research in fair and meaningful ways—both financially and symbolically.

Organizing Collectively: Alternative Governance

Rethinking governance in research projects can involve forming a diverse advisory committee, co-defining research questions, and collaboratively shaping dissemination methods. Consultation alone is not enough; true collaboration requires co-creation. In this spirit, putting intellectual property agreements in place is an essential form of protection. (A guide to write an agreement is available here for further guidance.) The goal is to clarify from the outset who owns what, how the results will be used, and how everyone’s contributions will be acknowledged.

Adopting a Stance of Listening and Self-Reflection

Engaging communities in a by-for-with approach requires humility. It means accepting that our usual ways of doing things may not always be adequate. It also means being open to transformation through connection, dialogue, and the realities we encounter.

This form of active listening calls for slowing down, cultivating genuine and lasting relationships, and sometimes stepping away from a project if conditions of respect, equity, and justice cannot be guaranteed. It’s not just about doing things well—it’s about doing no harm.

Rethinking research means rejecting extractivism, building authentic alliances, and honouring the diverse knowledge, experiences, and expertise of the people we work with.

Some excerpts are drawn from testimonies in the PSRR report or from the reflective card game. These have been adapted and anonymized for outreach purposes.

Promotion des actrices racisées en recherche (PARR). (2024). Strategies in bloom: Cultivate your well-being in collaborative research (Reflective card deck - English version). A tool for raising awareness and self-reflection, based on the testimonials and transformation ideas shared as part of the PARR project.

The definition of epistemic injustice is taken from the PARR report, which quotes Godrie, B., Desrosières, E., & al. (2020). Les injustices épistémiques : vers une reconnaissance des savoirs marginalisés.