The Need To Build Solidarity

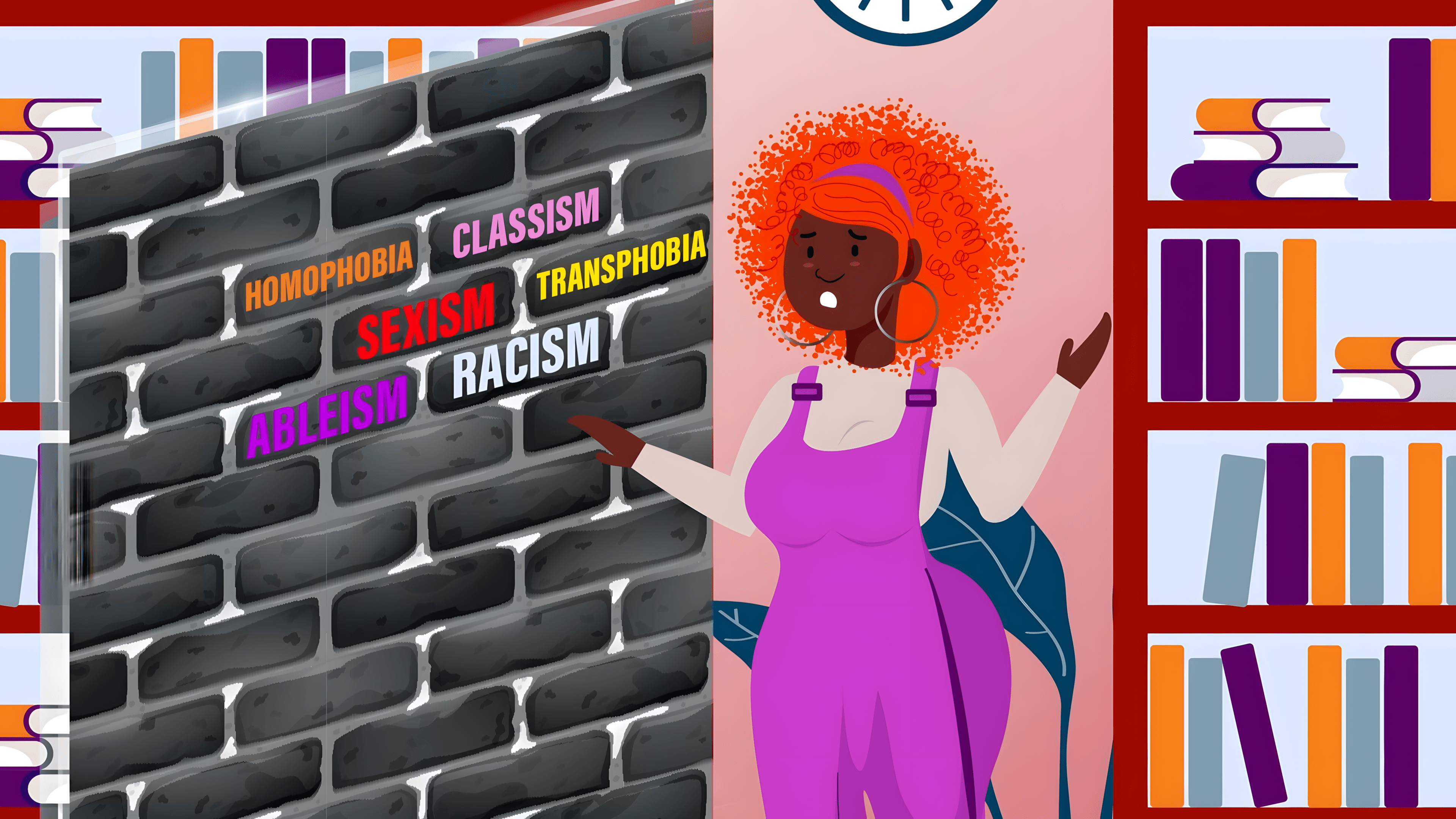

Why Isolation Is a Tool of the System

Isolation is not a simple accident—it is a systemic tactic designed to weaken marginalized people, discourage them, and erode their capacity to act. Cut off from connection, mutual support, and collective spaces, we become more vulnerable to structural violence.

This dynamic is especially acute in research settings. As highlighted by the PARR project, Black and racialized women and non-binary individuals engaged in participatory research face exclusion, instrumentalization, erasure, and marginalization. The lack of recognition for their knowledge, combined with the absence of tailored support networks, deepens their isolation and further undermines their power, agency and resilience.

Audre Lorde wrote it powerfully in Sister Outsider: “Without community, there is no liberation.” Similarly, the Combahee River Collective—a U.S.-based group of Black lesbian feminists—reminded us that “the only people who care enough about us to work consistently for our liberation are us.” In a world where dominant systems are designed to isolate, forging lasting connections and solidarity becomes a vital and radical political act.

From Isolation to Collective Power

At a PARR project workshop, one participant offered: “Don’t drain yourself trying to change an institution that doesn’t want to change. It leaves you empty and isolated.” This statement captures an often-shared reality: the immense pressure placed on Black and racialized women and gender-marginalized people in research—the exhausting struggle to change hostile structures all on their own.

But connection is more than an antidote to loneliness. It’s a force for transformation—turning individual experiences into collective strength. Through connection, we share our stories, move beyond shame, exchange strategies, and support one another’s survival. In coming together, our wounds are no longer private burdens—they become seeds of resistance.

Together, we can also begin to challenge institutional norms: the pressure to compete, to overproduce, to chase a narrow ideal of excellence. Spaces of mutual support allow us to cultivate a critical perspective, anchored in community and belonging.

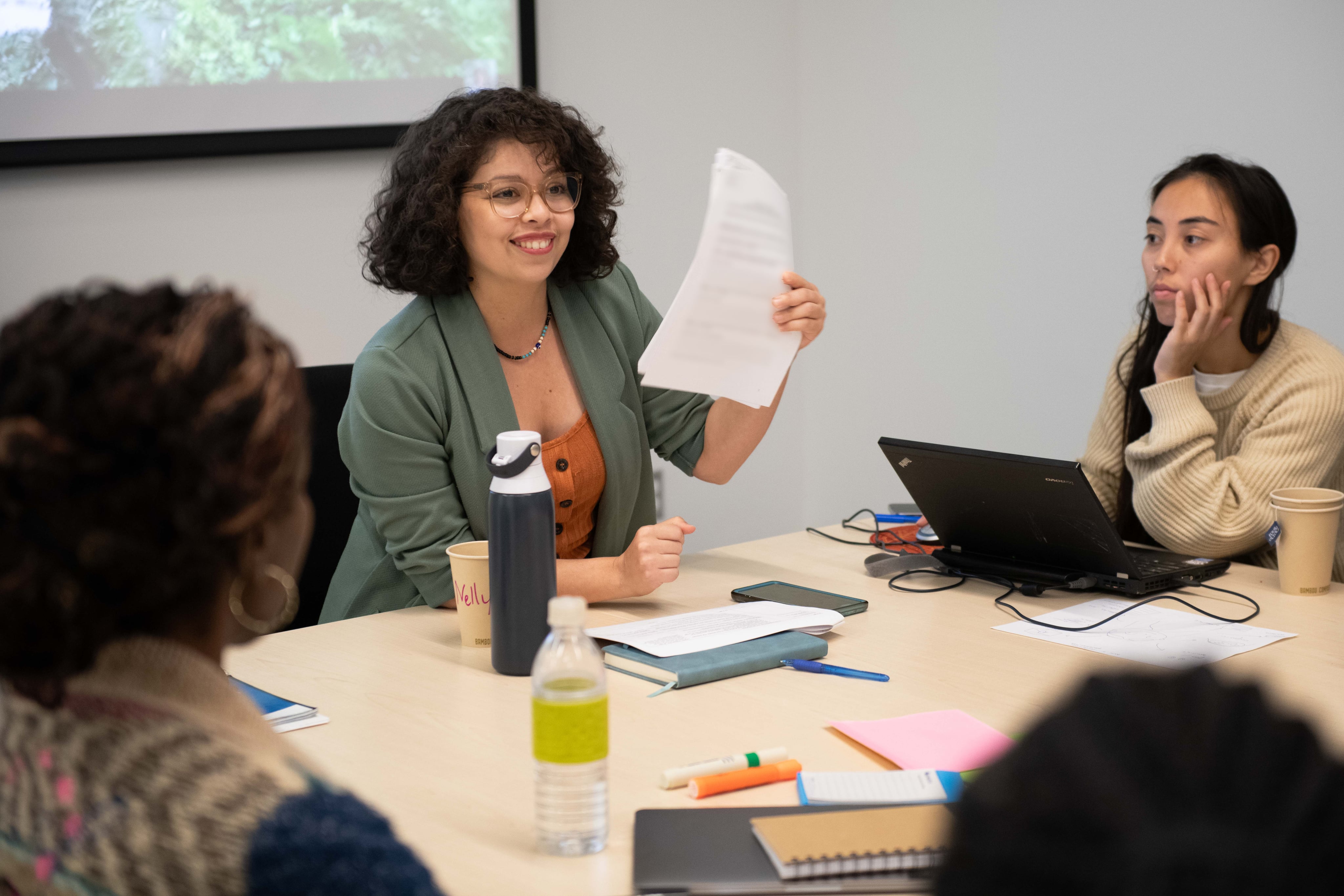

In the dialogue spaces created through the PARR project, participants’ testimonies brought to light experiences that are often silenced, while nurturing solidarity among those directly affected. For many, these spaces—by recognizing the value of situated knowledge and prioritizing emotional safety—helped restore a sense of legitimacy, offering both the strength and the language to speak out with renewed openness and confidence.

As Samia Dumais shared in episode 3 of the PARR podcast En fleurs, plus en feu !:

“My knowledge is valid. It was valid when I was an undergraduate student, during my master’s, and it still is today […]. Being able to connect with other participants in the PARR project and realizing that my interest in history is valid […] really gave me a boost—like wind in my sails—reminding me: okay, what I’m doing matters.”

In the same episode, Aurélie Milord eloquently explains that these moments of shared vulnerability among those directly affected not only help people feel heard and legitimate but also create openings within environments that are usually unreceptive to the complexity of lived oppression.

Expanding the Circle: Building Alliances Across Communities

While building connections within a single community is essential, extending solidarity across communities is just as vital—though often more complex. Colonial histories, differing experiences of oppression, intercommunity racism, and unresolved trauma all complicate the formation of genuine relationships.

Some participants in the BIPOC Days expressed that standing together is not without risks. It can be painful to constantly justify or explain one’s reality to others. There is also the risk of being instrumentalized, coupled with the uncomfortable burden of once again being expected to represent one’s entire community.

The political context, language barriers, and unequal access to funding further complicate efforts to build connections. Institutional competition for resources—driven and sustained by the neoliberal logic that governs the research sector—often pits us against one another rather than fostering solidarity.

Strategies for Building Bonds of Resistance

Despite these challenges, solidarity remains both possible and essential. How can it be nurtured? Here are some key approaches drawn from the diverse voices, reflections, and expertise shared during meetings and exchanges initiated by the PARR project over recent years.

1. Cultivate respect and compassionate listening.

Before embarking on joint projects, it’s crucial to establish relationships grounded in attentive listening and care. Asking questions like “What do you need right now?” and “What is most important for your community and group?” can create welcoming spaces without imposing agendas.

2. Stay open to being transformed by the relationship.

Solidarity requires openness to being challenged, shifting perspectives, and acknowledging blind spots. Recognizing and honouring the unique realities of each community is fundamental.

3. Name power dynamics.

A partnership is not automatically a collaboration. Another Black or racialized person is not necessarily an ally who will foster a relationship of fairness and reciprocal acknowledgment. Transparency is crucial: Who makes the decisions? Who benefits? What ethical framework do we establish to prevent extractivism or the reproduction of oppression?

4. Slow down.

Building solidarity is not a quick process. It takes time to cultivate genuine, lasting, and non-opportunistic bonds.

5. Build your toolkit and be strategic.

Creative practices—such as writing workshops, art therapy, and collective creation—can help overcome traditional communication barriers (language, language register, use of terms, etc.) that sometimes exist between diverse communities. These approaches open safer, more accessible spaces for sharing experiences that are often difficult to articulate in conventional or institutional settings.

6. Cultivate transparency and share resources.

Sharing information about funding opportunities, citing peers, and recommending one another—all these practices contribute to building a network that is more relational, rather than merely transactional.

Connecting with one another is no luxury; it is essential for our survival, the reclaiming of our power and capacity to act, along with our capacity to transform and protect ourselves from oppressive structures.

Through these bonds, we nurture a future rooted in hope, dignity, and justice. As bell hooks reminds us, there can be no healing without community.

By collectivizing our experiences and standing together, we are already beginning to change the world.

Some excerpts are drawn from testimonies in the PSRR report or from the reflective card game. These have been adapted and anonymized for outreach purposes.

Promotion des actrices racisées en recherche (PARR). (2024). Strategies in bloom: Cultivate your well-being in collaborative research (Reflective card deck - English version). A tool for raising awareness and self-reflection, based on the testimonials and transformation ideas shared as part of the PARR project.

The definition of epistemic injustice is taken from the PARR report, which quotes Godrie, B., Desrosières, E., & al. (2020). Les injustices épistémiques : vers une reconnaissance des savoirs marginalisés.