Black and Racialized Women and Non-Binary People in Partnership-Based Research

Invisible, but not absent. This insight is what sparked the creation of the PARR project. In the 1st episode of the podcast En fleurs, Plus en feu !, Alexandra Pierre reflects on this, recalling the questions that shaped the project’s beginnings: “I’d be really surprised if racialized women and non-binary people hadn’t written or thought about this—but clearly, it’s not visible, and it’s not something we can easily access.” What’s missing isn’t thought or reflection—it’s access to spaces, recognition, and opportunities for sharing that knowledge. Far too often, the voices, knowledge, lived experiences, and contributions of those directly concerned remain sidelined in research—even within spaces that claim to be inclusive.

The gap between demographic presence and representation in knowledge production is stark. In Quebec, racialized people make up approximately 16% of the population (and nearly 38% in Montreal, according to the 2021 Census). Yet, as noted in the literature review from the PARR research report, Black and racialized women and non-binary people remain largely absent from the academic literature, especially in the context of partnership-based research. Their contributions are under-documented, underutilized, and rarely acknowledged as valid forms of knowledge in their own right.

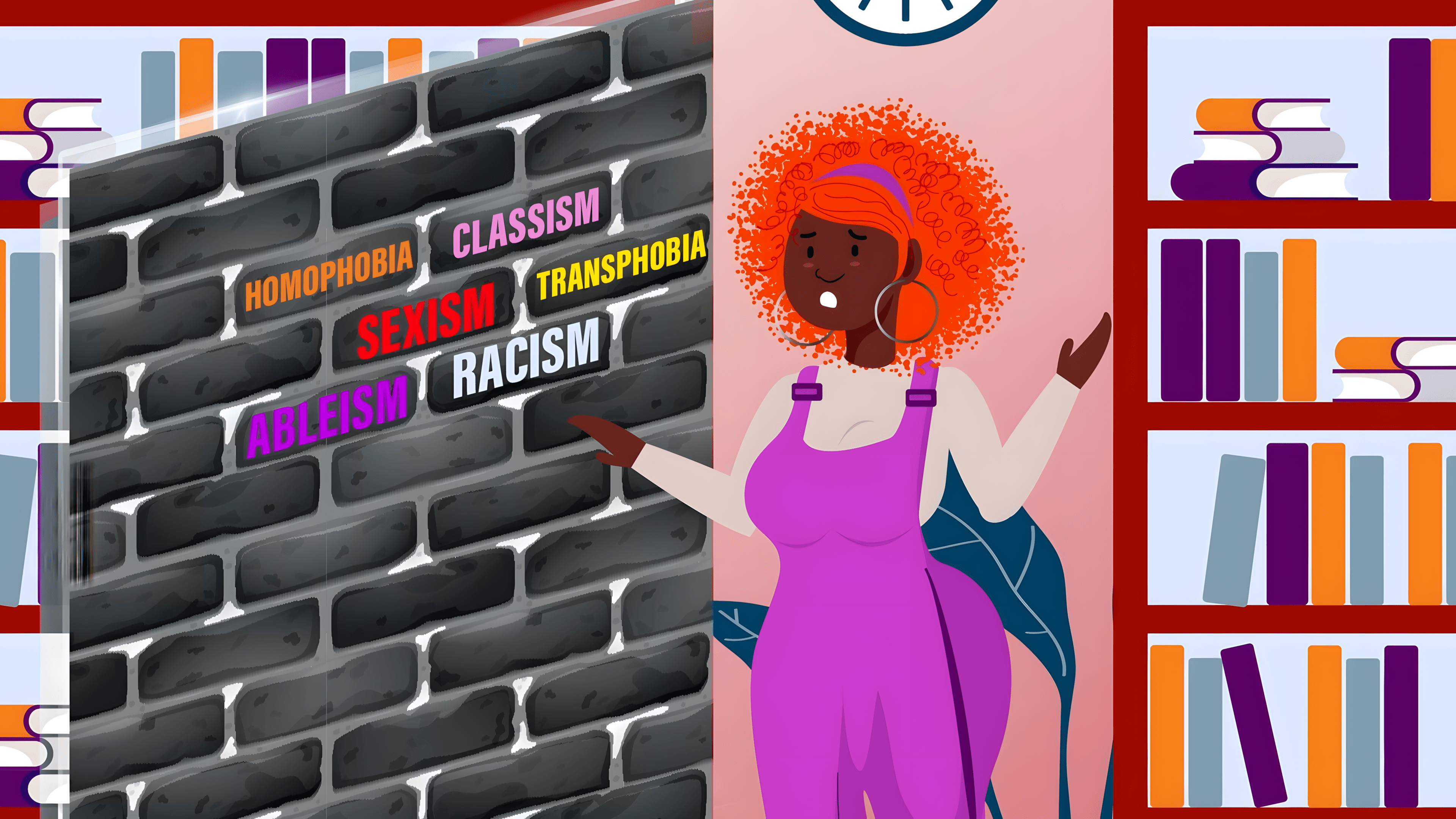

This structural invisibilization is no coincidence. It is the product of a system in which dominant forms of knowledge are continuously reproduced by the same actors, within the same institutions, following the same codes.

Erased from the Start

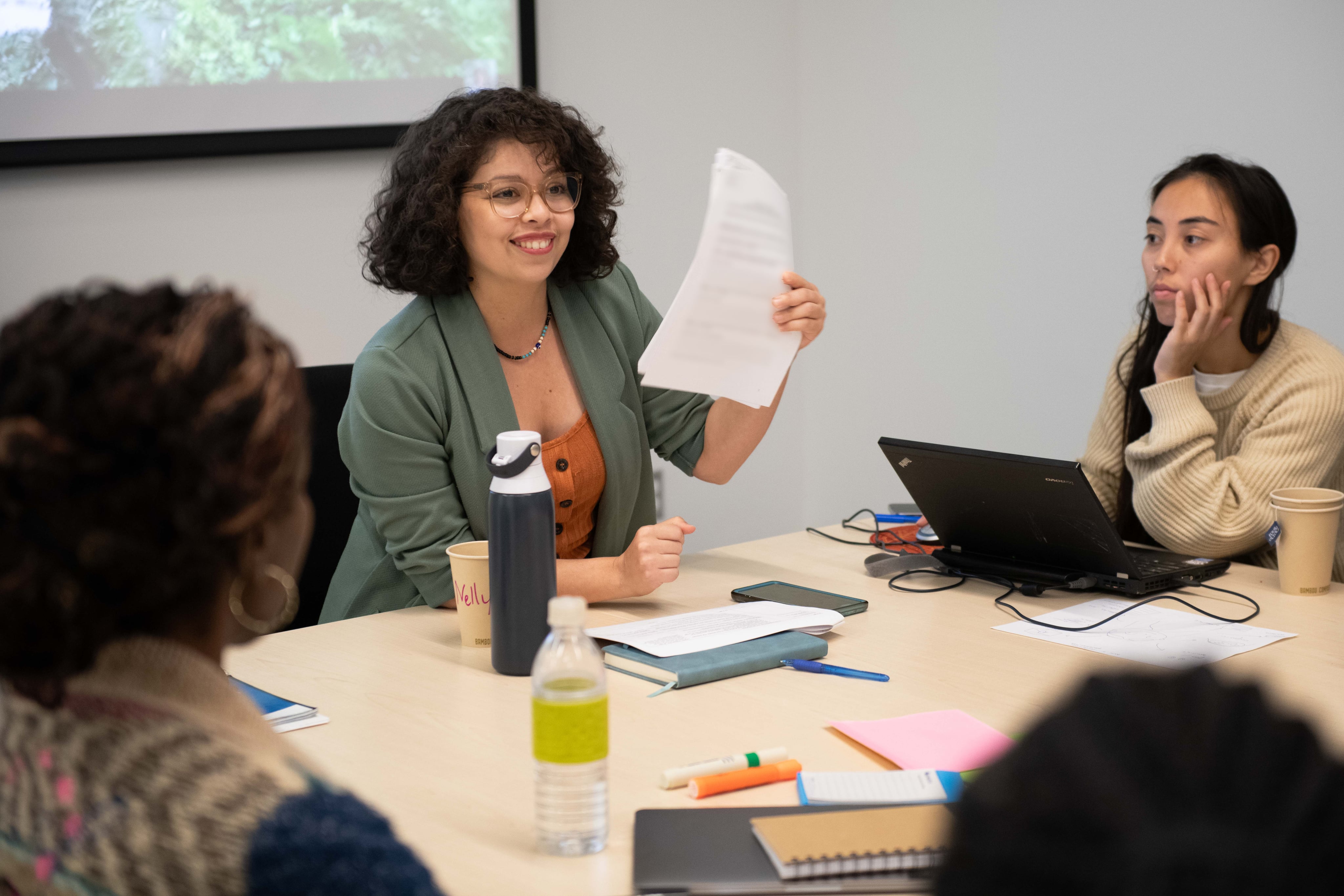

From the very beginning of the PARR project, one question kept resurfacing: Where are Black and racialized people in partnership-based research? And just as importantly: What are their experiences when they do participate? To explore these questions, the project adopted a rigorous methodological approach, guided by an advisory committee made up of individuals from both community and academic settings who are attuned to epistemic injustice—namely, the devaluation and invisibilization of knowledge produced by marginalized people. Recruitment was designed to reflect a diversity of experiences and expertise, often overlooked in existing research.

Participant mapping conducted through PARR research revealed a wide range of geographic backgrounds, life paths, and fields of engagement. Despite this diversity, many participants reported a common experience: a profound sense of isolation tied to their minority status in research environments. Being “the only one” on a team or around a table is far from trivial. It affects perceived legitimacy, how attentively one is heard, and the roles one is assigned—often limited to symbolic presence or cultural interpretation. As Chloé, a political science PhD student who took part in the research, explained: “As a doctoral student working on a topic like mine, […] I often feel very isolated. When I walk into a room full of researchers, I’m often the only Black person there.”

For Éva, another participant, this isolation is compounded by its internalization: “We start to believe that research is a world reserved for a certain kind of person and […] those beliefs start to shape other areas of our lives. And maybe that holds us back from pursuing our goals…”

In Research, But Not Fully Recognized

Participating in a research project doesn’t automatically lead to full and meaningful recognition. Findings from the PARR project reveal that many Black and racialized women and non-binary people have had their contributions marginalized—or even erased—within knowledge production processes. Some formulated research questions, mobilized networks, and raised sensitive issues in complex contexts—yet were not regarded as legitimate co-creators of knowledge.

Romy, one of the project participants, articulates the disconnect between expectations and actual recognition: “I kept asking myself… do they think I’m the administrative assistant? […] People would turn to me when the conversation was about logistics […] but when it came to contributing ideas […] there was always this surprised look when I said something people found relevant.”

This form of erasure is part of a broader history of epistemic injustice, in which marginalized forms of knowledge are discredited, instrumentalized, or excluded because they don’t align with dominant norms of what counts as worthy—or “good”—knowledge. These norms, deeply rooted in academic settings, are rarely challenged in partnership-based collaborations—often reproducing the very inequalities such projects aim to address.

Documenting, Making Visible, Valuing

The PARR project chose to document these experiences not as isolated incidents, but as indicators of a system that must be transformed. Through this research, a vital contribution was made to Quebec’s literature, shedding light on life paths that have long been overlooked or silenced.

Including Black and racialized women and non-binary people in partnership-based research is not simply a matter of “diversifying” teams. It means questioning who gets to decide, who is recognized as knowledgeable, and who holds the power to shape meaning. It also means valuing situated knowledge—those grounded in lived experience at the intersections of multiple systems of oppression. Most importantly, it means creating the conditions for these individuals not only to be present, but to be listened to, respected, and fully recognized.

Voices like Ella Martindale’s, featured in episode 4 of the podcast En fleurs, Plus en feu !, invite us to radically reimagine our research posture: “For example, I go into a community and say: I’d like to study—with you—the river near where you live, the one you all go to together. Then I ask: What do you do here? What does this river mean to you? How do you experience it? The river is just one example—it could be a school, or any other place. What matters is that people define the place, and in turn, the place helps define them.”

This kind of indirect approach helps avoid retraumatizing narratives, reductive identity assignments, and repetitive storytelling. As she explains: “ i’m not as interested [...] in trying to define people or trying to get the lived experience of a certain kind of person. Instead i’m trying to figure out how we are living together, what we are doing in place, what our actions are, what our practices are, what our community looks like, what’s important to us, like all of those things [...]. Like looking more into the future [...]. The frame of our research is really important, [...] It gets us away from some of the stereotypes we might reinforce, so the histories that we might retell over and over again, that like our community doesn’t need to hear”

The trajectories documented through the PARR project are neither marginal nor anecdotal. Taken together, they represent a collective body of knowledge—one that reveals not only the mechanisms of exclusion but also practices of resilience and new aspirations. Acknowledging the role of Black and racialized women and non-binary people in partnership-based research means recognizing their knowledge, lived realities, concerns, and their visions for imagining and building different futures.

Some excerpts are drawn from testimonies in the PSRR report or from the reflective card game. These have been adapted and anonymized for outreach purposes.

Promotion des actrices racisées en recherche (PARR). (2024). Strategies in bloom: Cultivate your well-being in collaborative research (Reflective card deck - English version). A tool for raising awareness and self-reflection, based on the testimonials and transformation ideas shared as part of the PARR project.

The definition of epistemic injustice is taken from the PARR report, which quotes Godrie, B., Desrosières, E., & al. (2020). Les injustices épistémiques : vers une reconnaissance des savoirs marginalisés.